An Abundance of Beaches and Streams

Each watershed in the region has its own unique personality – those characteristics that make it special to live in, for both the people and the wildlife who live here.

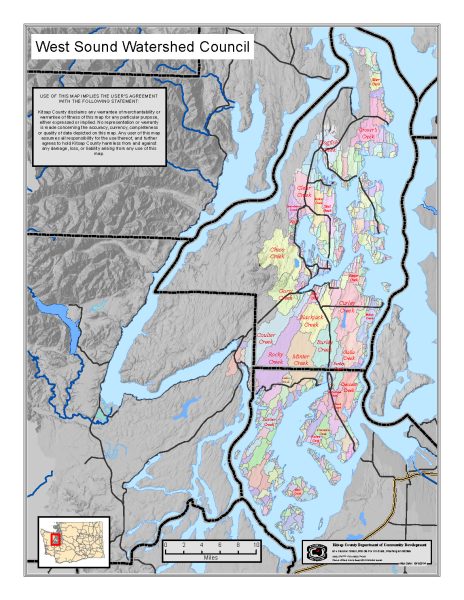

The defining feature of the West Sound Watersheds is its shorelines – over 360 miles of shoreline. These shores contain islands such as the Bainbridge and McNeil islands, and peninsulas such as the Key Peninsula and Gig Harbor peninsula. There are islands, bays, inlets and bluffs throughout the area. The tide flats and rocky outcrops play host to an incredible bounty of wildlife. For salmon, those shoreline areas are a vital nursery area for outgoing juvenile Chinook salmon from throughout Puget Sound.

Another important feature about this watershed is that it’s not just one watershed, but actually a series of nearly 120 watersheds. These small, independent watersheds are each drained by a small to medium-sized creek that flows directly into the Puget Sound. This contrasts to other Puget Sound watersheds, such as the Green-Duwamish, that are characterized by a single large river that drains a large watershed. These smaller streams are great habitat for salmon such as chum, coho and steelhead.

An Abundance of Beaches and Streams

Each watershed in the region has its own unique personality – those characteristics that make it special to live in, for both the people and the wildlife who live here.

The defining feature of the West Sound Watersheds is its shorelines – over 360 miles of shoreline. These shores contain islands such as the Bainbridge and McNeil islands, and peninsulas such as the Key Peninsula and Gig Harbor peninsula. There are islands, bays, inlets and bluffs throughout the area. The tide flats and rocky outcrops play host to an incredible bounty of wildlife. For salmon, those shoreline areas are a vital nursery area for outgoing juvenile Chinook salmon from throughout Puget Sound.

Another important feature about this watershed is that it’s not just one watershed, but actually a series of nearly 120 watersheds. These small, independent watersheds are each drained by a small to medium-sized creek that flows directly into the Puget Sound. This contrasts to other Puget Sound watersheds, such as the Green-Duwamish, that are characterized by a single large river that drains a large watershed. These smaller streams are great habitat for salmon such as chum, coho and steelhead.

The Challenges of Bulkheads, Ditches and Barriers

The development of this area has allowed the communities to flourish – but it has provided challenges to the fish and other habitat.

On the shorelines, bulkheads have proliferated. It is estimated that 56% of the shoreline in the area (PDF) is modified by bulkheads, roads, or other structures. Bulkheads are hard for nearshore habitat in a number of ways. First, they shorten the beach areas where the so-called forage fish (sand lance, surf smelt, and pacific herring) spawn. These fish are the base of the foodweb, supporting salmon, Orcas and many other species. Second, they limit the amount of wood and natural wrack that can be on the beach – which are areas where juvenile salmon can hide from predators and find food.

On the streams themselves, clearing the land for agriculture and development often meant straightening the streams, and cutting them off from off-channel and wetland areas that are vital for young salmon to grow and find food. Other streams that naturally would have flowed into an estuary were disconnected from the tide.

There are also numerous roads and other barriers that partially or fully block salmon from returning back upstream to spawn. This means that even if there is good habitat upstream, the fish can’t get access it. Sometimes it’s because the water flowing through the pipe is flowing too fast, or because the angle is too steep.

With Community Support, Past Mistakes are Fixed

The communities of the West Sound Watersheds have been brought together with a passion for restoring the health of their fish. Through neighborhood groups, or the larger salmon recovery efforts of the West Sound Watershed Council, people are restoring the many ways that these watersheds need to function.

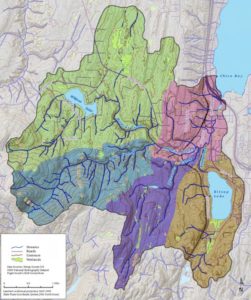

One area where the community has focused efforts is Chico Creek. Chico Creek, with its tributaries, is the most productive salmon streams on the Kitsap Peninsula, supporting spawning and rearing populations of chum, coho, steelhead, and coastal cutthroat. This watershed includes 50 miles of stream channels (including tributary streams such as Kitsap Creek, Dickerson Creek, Lost Creek, and Wildcat Creek) and two large lakes (Kitsap Lake and Wildcat Lake).

The Kitsap Conservation District has worked on a number of backyard restoration projects throughout the watershed, and recently a project replaced a road with a bridge for better fish passage at Taylor road.

And right now, a fish passage barrier created by Hwy 3 is being prepared for construction.

The Chico Creek watershed

(Chico Creek Watershed Assessment for the Identification of Protection and Restoration Actions: The Suquamish Tribe)

Salmon in Chico Creek

An example of a projects in this watershed

- Dickerson Creek Culvert Replacement & Floodplain Restoration: This project will replace two aging road culverts with larger fish-passable culverts, remove streambank armoring, restore floodplain habitat and off-channel areas, enhance in-stream and riparian conditions, reduce flooding, and provide public education opportunities. The habitat upstream of the project site is identified as some of the best spawning and rearing habitat for chum salmon in the Chico Creek watershed.

New culvert going in

New habitat in Dickerson Creek

- Chico Creek Fish Passage and Instream Restoration at Golf Club Hill Rd: The project will replace the short concrete box culvert with a 140-foot span bridge, widening the stream channel and allowing for the fish to migrate more easily. Work will also include some streambed restoration, including removing weirs downstream and adding natural wood debris. Kitsap County Public Works and the Suquamish Tribe are joining together for a $4.4 million project that will opening up miles of habitat for salmon to spawn.

A triple-box culvert underneath Golf Club Hill Road, ranked as the county’s top barrier to fish migration,

is set to be replaced with a 140-foot bridge. (Photo: Josh Farley)

Another focus of work to restore salmon is in the Curley Creek Watershed, located near Port Orchard. The watershed drains an area encompassing 15 square miles. Long Lake, located near the center of the watershed, stretches nearly 2 miles in length, and Salmonberry Creek is an important tributary.

Curley Creek is an important salmon stream home to coho, both fall and summer runs of chum, and coastal cutthroat trout. It is also important habitat for two species listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act: steelhead and Chinook salmon.

The Curley Creek Watershed Map

(The Curley Creek Watershed Assessment and Restoration Plan: The Suquamish Tribe)

An example of a project in this watershed is Salmonberry Creek

- Salmonberry Wetland Enhancement : The stretch of Salmonberry Creek that flowed in Port Orchard, Washington had been turned into a ditch. This project created a new channel for the stream, one that would meander and have pools for the fish to take refuge during winter high flows.

Before

After

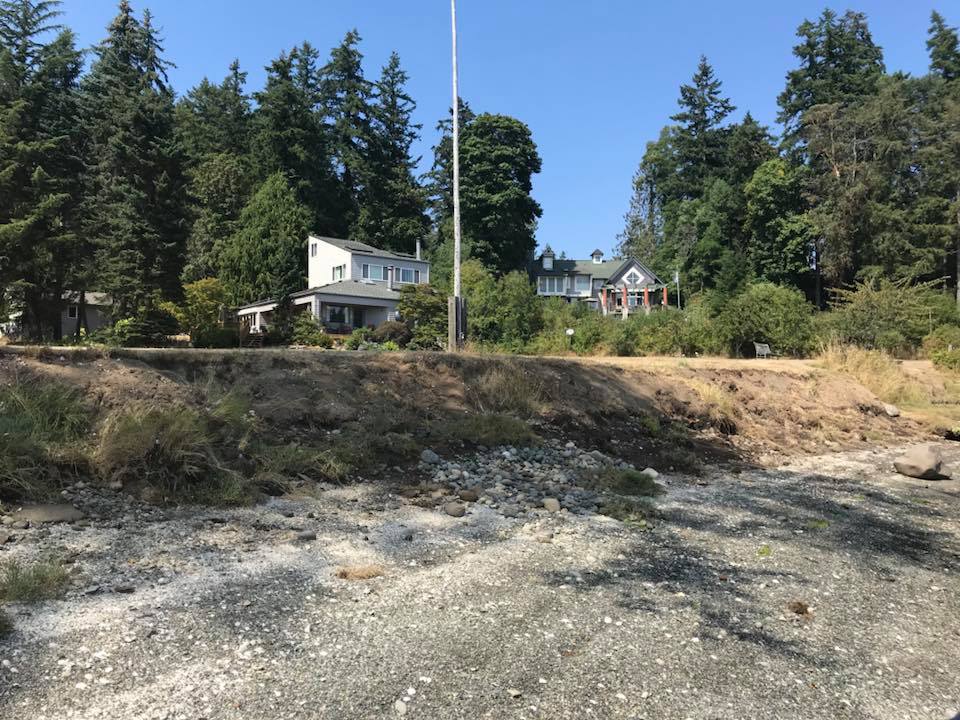

The shoreline is also a focus of restoration work, with an aim toward removing bulkheads and restoring estuaries.

- Arnold Shoreline Restoration: Mid Sound worked with a private landowner in Bremerton who wanted to remove his failing bulkhead and a few pilings from the shoreline and then to plant some native plants along the restored shoreline.

Before

After

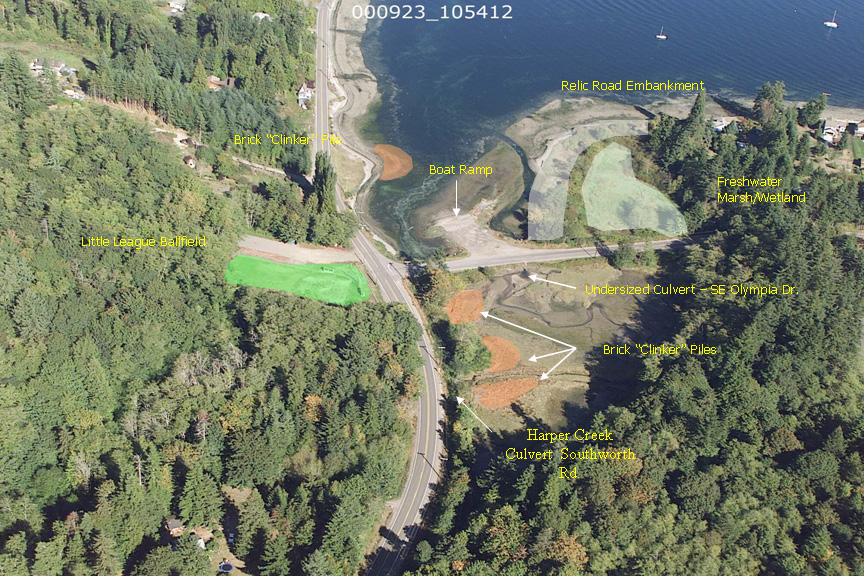

- Harper Estuary Restoration: Harper Estuary important value for fish and wildlife, recreation and local history. The Harper Estuary Restoration Project aims to re-stablish tidal influence and estuarine habitat. Restoration continues to progress with the completion of phase one work and launching of phase two work. Phase one work:

- Replaced the under-sized culvert on Southworth Drive with a 16-foot wide box culvert;

- Removed bricks, contaminated industrial fill, and a concrete bulkhead;

- Created a tidal connection to the wetland east of the Olympiad culvert; and

- Added large woody debris on newly shaped spit and installed plants.

Phase two work

- the construction of a new 120-foot bridge over the estuary to replace the undersized culvert at Olympiad Drive, and

- restore tidal influences.

Restoration Detail

Before

After

Fish

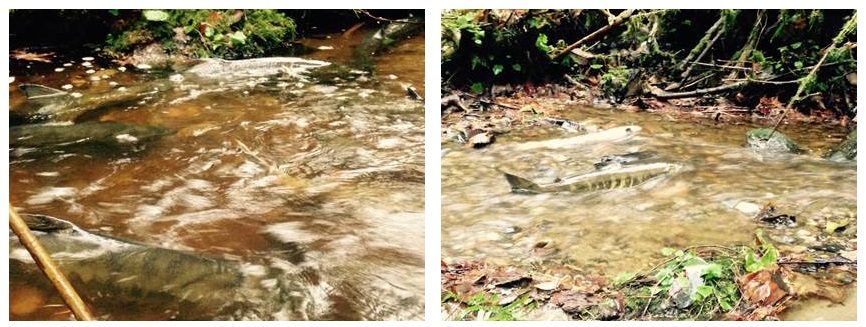

Approximately 89 of the streams in the area support spawning populations of salmon – including chum, Coho, steelhead and cutthroat trout. These streams have supported strong populations of salmon because of the abundance of wetlands associated with their habitats.

Historically, chum and Coho have teemed in these rivers, providing a staple food for native tribes such as the Suquamish Tribe. These fish still return to many streams, such as these Chum returning to Cowling Creek.

Vital Shorelines

While the streams provide spawning habitat for some salmon, the miles of shoreline provide vital habitat for juvenile Chinook salmon from other larger rivers in the Puget Sound. These young fish often spend months in this area eating and growing before heading out into the open ocean.

One of the reasons that young salmon flock to this area is because these beaches are spawning grounds for so-called “forage fish.” Forage fish are the small fish (Pacific Herring, Surf Smelt, and Sand Lance) that many other species feed on; they are the base of the food chain. Because they spawn in the sand and gravel of tidal areas, natural erosion and gravel movement is important to the health of the populations.

This image shows an example of “forage fish” such as herring that are a significant source of food for salmon and other, more large fish. Picture courtesy of Flickr user Ingrid Taylar.

Shoreline vegetation and natural eel grass beds are also important to wild salmon. The land vegetation provides shade and falling bugs that feed the young salmon. Eel grass provides important places to hide and find food for salmon smolt.

Protection Efforts

The local governments, tribes, citizens, and nonprofits are working together through the West Sound Watersheds Council to prioritize restoration and protection for the future of all the fish that live in the area. These habitat restoration priorities are part of the larger restoration priorities of the West Central Local Integrating Organization.

Landowners are learning how to voluntarily restore their shorelines through the collaborative Shore Friendly effort.

Mid Sound’s work

Mid Sound completed restoration projects in several of the local creeks, including Barker Creek, Gorst Creek, and Salmonberry Creek. We are currently working on Cowling Creek.

What You Can Do

Do you live in the West Sound watershed? Check out our What You Can Do page for more tips on actions you can take to help salmon whether you live on a stream, a lake, a beach or elsewhere in the watershed.

You can see fish in the streams in fall each year. Kitsap Salmon Tours has a list of great viewing sites.